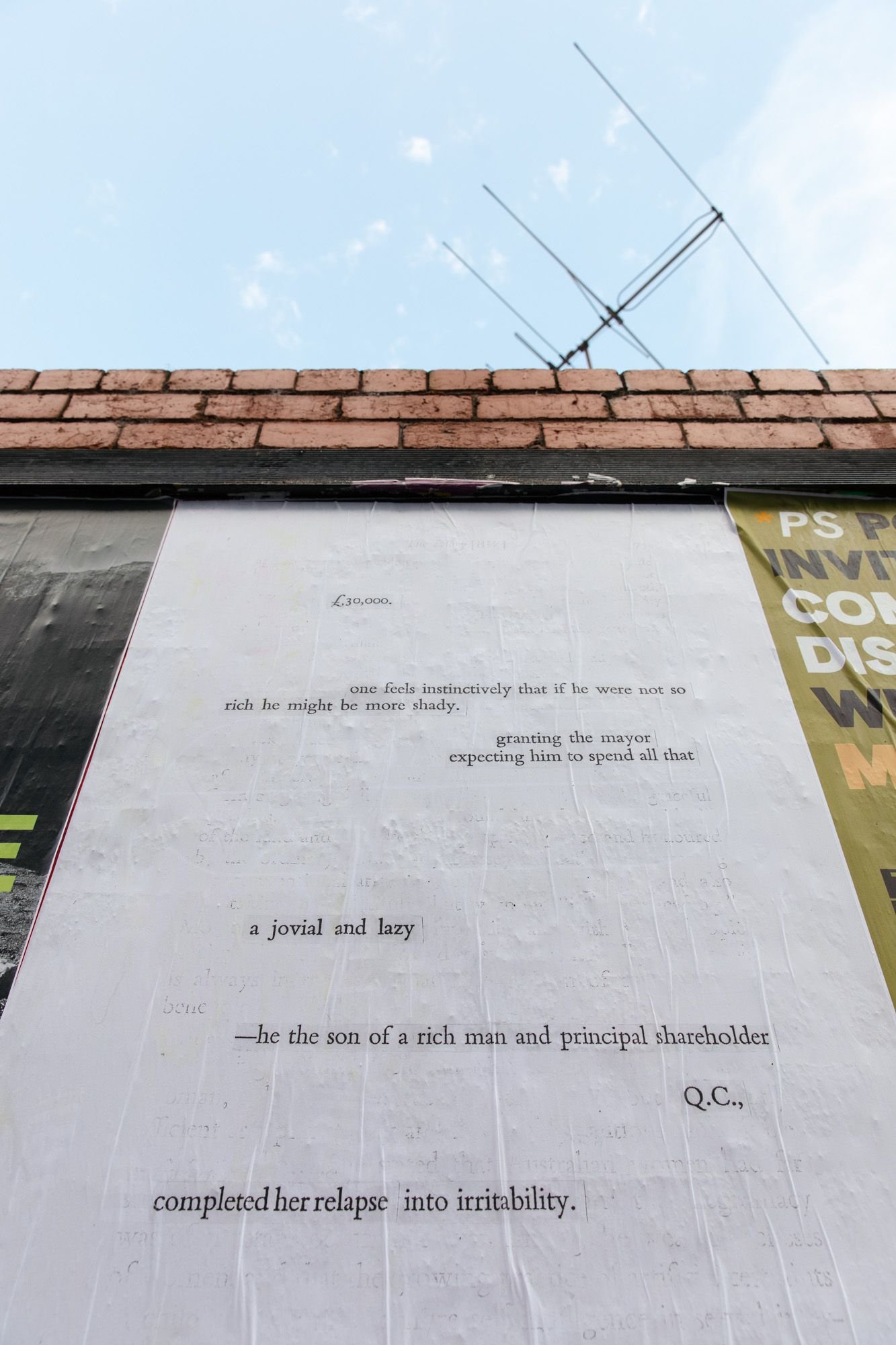

As Linden Gallery’s writer-in-residence, Dr Lucinda Strahan (aka expanded Non/FICTION expert, writer, researcher, lecturer) harnessed the radical energy, DIY ethos and countercultural spirit of punk and feminism for her exhibition “a rather gross materialism”. Through a playful process she calls “poetic erasure” she reinterpreted source text from the colonial record The Webbs’ Australian Diary 1898 using collage and text pairing to remake, reimagine and subvert the subjectivities and cultural narratives of the diary. Strahan then compiled a suite of xeroxed posters that extended beyond the gallery walls and were pasted up and appeared outdoors on billboards scattered around St Kilda.

As she explains:

“I was first drawn to the voice of Beatrice Webb when she was quoted in another historical text, saying of the “well-to-do women” of Australia: “certainly these colonial women are in an unpleasant stage of development…vapid in talk without public spirit or intellectual sympathies” they were “uncommonly inferior to the men” and “the least worthy product of Australia”. The weird misogyny of this statement felt familiar and historically true, and its absurd almost Wildean turn of phrase made me laugh out loud. I immediately started searching for the source text.

Beatrice and Sidney Webb were well-known British public intellectuals. They were socialists and labour reformers; affluent leftists who co-founded the London School of Economics. The Webbs took great interest in the colonial “experiment”, and during their journey to Australia in 1898, met and spoke with almost all the leading political and social figures of the time. The Webbs’ Australian Diary 1898 is their travel journal, published posthumously in the 1950s.

The diary is, as I had hoped, a gold mine of found-words. Beatrice Webb’s impressions of Australian society, its ruling class, its political leaders and industrial barons, are expressed in anachronistic language that frequently tips into camp. But her expertise as a sociologist and political scientist means that even her blatant bad-moodism carries historical weight.

As it turns out, it was not just the wealthy colonial women who gave Beatrice Webb the shits during her visit. Almost everything else did too. As I worked with the text of the diary, I found myself identifying with her cranky observations about the “rather gross” materialism of the emerging society—exceedingly rich and anti-intellectual, gorging on mining, led by dull men. Her frequent “relapse into irritability” reminded me of my own despairing moments over the contemporary social and political climate. In this way I began to identify with Beatrice Webb’s voice, and her straight-talking insults even as I disagreed with her views on women, on race and her obvious acceptance of the colony as ‘terra nullius’.”

I was lucky enough to document Lucinda (and her spunky chihuahua Gina) in the early days of the project as she cut and compiled the collages and once again a little further down the track when the paste ups appeared in the local neighbourhood.